Like Charles Kingsford Smith, Billie Sinclair came into the world of flying at its glorious dawn. On October 3rd, 1932, fourteen-year-old Billie – the only deaf and blind child among students from the NSW Institute for Deaf, Dumb and Blind Children – receives a joy flight from the famous aviator. Strapped to a board in Smithy’s Fokker trimotor, the Southern Cross, Billie experiences flight as “like a big elevator going up in a store.” He feels like an “uncaged bird” as wind rushes over his face, clean and fresh. This glorious day marks the first in his family to fly.

Billie wasn’t always deaf and blind. His family left Glasgow in 1920, sailing on the SS Megantic to Sydney when he was two. The ship carried a deadly stowaway – measles – which spread among passengers. When they docked at Woolloomooloo Wharf on February 26th, an ambulance rushed the desperately ill boy to hospital. Billie recovered but was left totally deaf at the critical time of language learning. In 1920, thirty percent of those with measles suffered serious complications. Billie’s parents checked “measles” as the cause of his hearing loss on his Institution enrolment forms.

At age five, Billie began boarding at the Institution in Darlington House, Newtown. Here he learned fingerspelling based on British Sign Language’s touch alphabet, becoming reputedly the fastest finger speller in the world. His family never learned to communicate with him this way. “I speak with my hands,” he would say, yet spent most of the year away from home.

Catastrophe struck in 1928. A bookcase fell on ten-year-old Billie’s head, leaving him completely blind. “The last thing I see is probably my own fingers spread out against the light.” Now he had to learn Braille, relying entirely on touch, taste, and smell to navigate the world.

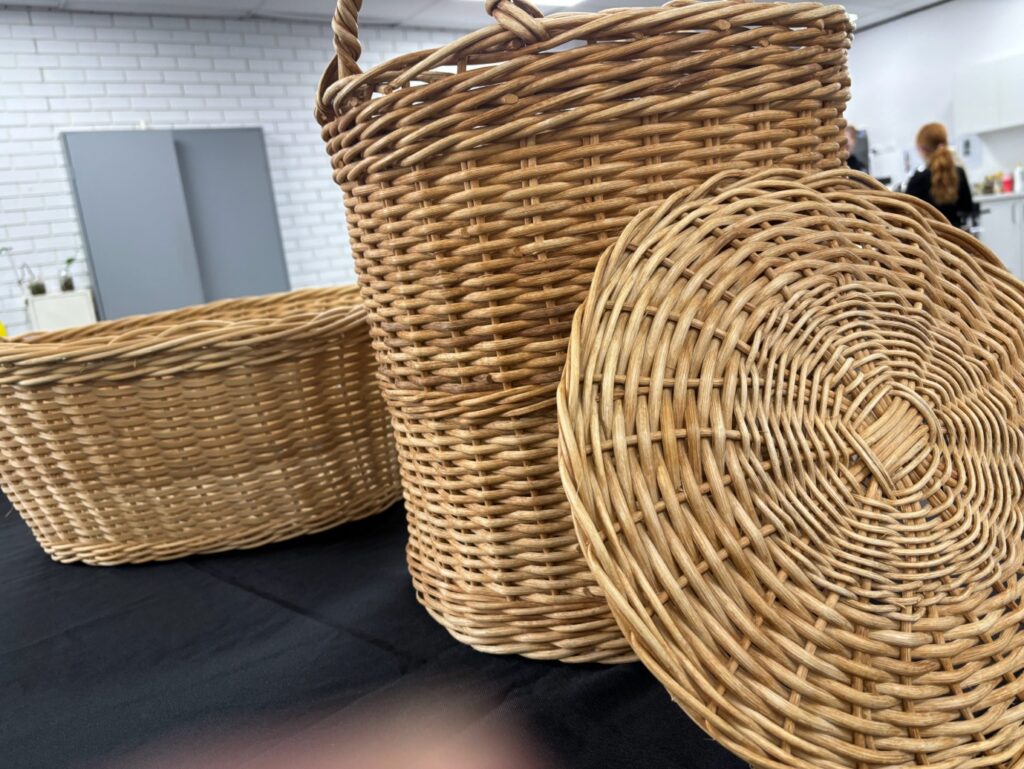

After leaving school at seventeen, Billie worked at Mitchell Workshop, weaving mats for the Army and Navy, later making baskets and laundry bags. “Basket weaving is my favourite kind of work and selling them gives me the money to travel,” he said. “Although I have been making baskets for more than sixty years, I have never seen even one of them.”

In 1990, the Institution sold Mitchell Manufacturing, viewing ‘sheltered workshops’ as undignified. Billie was devastated by forced retirement at seventy-two. “I don’t use a mirror. So I don’t consider myself old,” he protested. He continued making over 1,000 items in his spare time – everyone who knew him treasured their “Billie basket.”

Helen Keller visited Sydney in 1949, running her fingers over thirty-one-year-old Billie’s face and declaring, “Oh my, what a handsome man.” This encounter showed Billie that deafblind people could be world travellers.

Billie became a founder of the Deafblind Association (NSW), naming the ‘Hand over Hand Club’ and ‘Rainbow News.’ He lived at Lonsdale Hostel, Stanmore, at the heart of a thriving deaf community where everyone understood tactile communication. His bright basement room with ceiling windows became his workshop, where sunlight warmed his face as he softened cane strands and wove them into baskets.

In 1992, filmmaker Christopher Tuckfield created the documentary “The Journey” about Billie, taking him to Japan with cinematographer Dion Beebe. The film explored what travel meant to someone deaf and blind. “My parents kept me inside, so I feel like I have been let out of a cage,” Billie explained. He drew pictures during filming – including the bookcase falling, elephants he remembered from before, and a slightly broken heart from a woman he once loved.

From 1980 onwards, Billie travelled extensively: Scotland, England, Europe, USA, Singapore, Tibet, China, Thailand, Philippines, Japan twice, and finally New Zealand in 2001. He collected sensory memories – the feel of buildings in the Philippines, water on skin in Japan, elephant rides in Tibet, Thai massages, touching Louis Braille’s globe in France, and the rush of rollercoasters in America. “The best rollercoaster in the world is Space Mountain,” he declared. “I’m told people find the scariest bits are in the dark. I imagine the shape as I go around.”

In 1995, everything changed. The Deaf Society sold their Stanmore headquarters, relocating hostel residents to Mullauna Lodge in Blacktown. Billie, now seventy-five, lost his supportive community. The new facility had minimal deafblind communication training. Though the food was good, isolation began taking its toll.

After suffering strokes in 2004, Billie’s health deteriorated. Hospital staff were too busy and ignorant to communicate properly. No signs indicated he was deaf and blind; meals arrived and were removed untouched because no one told him they were there. A stroke damaged sensation in his left hand, cutting off his primary communication method, yet no one informed his interpreters.

Without consultation, Billie was moved to Mayflower nursing home in Westmead. Visitors found him desperate: “I am so hungry nobody brought me anything to eat.” Staff wouldn’t even use simple “print on palm” communication. “No one bothered about him at all,” said Janne from Deafblind NSW.

Billie Sinclair died on February 25th, 2005, aged eighty-seven. One hundred people gathered at the Uniting Church to mourn. There were memories of his travels, baskets, chess games, and impeccable dress sense – always in collar and tie, even for emergencies. But there was also anger at his treatment in hospital and nursing home.

Tony Hirst from Deafblind NSW wrote: “He simply wasted away from loneliness. I don’t believe the 25th of February 2005 would have been Billie’s day of reckoning if his communication needs and mental stimulation needs had been met.”

“The Journey” won awards at major film festivals worldwide. As long as people watch the documentary, Billie continues travelling. The fastest finger-speller in the world lived a life of perpetual motion, from that first flight with Smithy in 1932 to his final journey – a testament to the human spirit’s refusal to be caged.

You can see the film The Journey at the National Conference on dual sensory impairment-deafblindness: Filling in the gaps and joining the dots.

After the screening, there will be a Q&A chat with the director Chris Tuckfield.

Date: 27th and 28th November 2025

Time:

27th: 9am – 7pm (film screening at 5:15pm on the 27th)

28th: 8:30am – 5pm

Where: Susan Wakil Health Building, The University of Sydney